The Seventh Element: Palliative Care as the core essence of Medicine and Science

– Dr. Ravi Kiran Pothamsetty, Madurai

World Compassion Day (WCD 2025) is celebrated annually on November 28, intended not merely as a day of symbolic gestures, but as a call to embrace a truly compassionate lifestyle that honors all living beings with respect, empathy, and care.

On this observance, I take a moment to reflect on my personal landscape to recognize how the essence of palliative care is quietly woven into our everyday lives, in how we listen, comfort, and connect with one another beyond words.

My connection with my grandmother was not only emotional but profoundly inspirational. She was the reason I chose to become a doctor, more precisely, a healer. I can still hear her words, “Let there be at least one doctor in our family, someone who would serve with purpose and divinity”. Those words stayed with me through medical school and beyond.

Years passed. My granny became old, fragile and demented. Yet, in her memory, I remained the playful schoolboy who would run around her room. We cared for her, nurtured her like a baby and decided to go against futile medical care that would have prolonged her suffering. There was no regret, just the righteous act of knowing we said goodbye, guilt-free, and remembered her in her last days with peace. That experience introduced me to palliative care and helped me absorb what it truly means to care beyond prescriptions and procedures.

As time moved on, I became an oncologist holding responsibility to make decisions, manage disease, and explain treatment algorithms. Yet, deep inside me, I often whispered, “Am I really doing the right thing for this person, right now?” That quiet moment with my grandmother had planted a seed that slowly began to take its shape.

I slowly realized that some of the most healing moments I witnessed with my patients could never be measured on a scale or in numbers. Every pain matter, and every story deserves a dignified and meaningful closure. Over the years, my patients have become my greatest mentors.

A few months ago, a 64-year-old person with metastatic breast cancer post multiple lines of chemotherapy failure, declared end of life care, and eventually slipped into an unresponsive state. We counselled regarding her illness trajectories and anticipatory outcomes but the words I never forget. “Is this the maximum you can offer? Her son looked at me and asked, “How am I supposed to face my father that I have given up by signing DNR?” He wasn’t angry. That unexpected vulnerability stayed with me.

We were always taught the opposite of success is failure. But in palliative medicine, we learn something deeper: the opposite of success is not being adaptable. A living will, a DNR, or hospice care is not giving up. They are part of the continuum of care. Just like we transition from childhood to old age, our needs and decisions change. We don’t abandon; we adapt.

When survival is no longer possible, changing goals is standing up for the patient. I remember telling him, saying no to CPR does not mean withdrawing treatment. It means honoring your mother’s journey by choosing not to cause more harm when things were uncertain. That eased his internal conflict and reaffirmed my belief that palliative care is not the absence of action, but the presence of wisdom.

Not all suffering is spoken and not every goodbye is questioned. Around the same time, I met a mother of three- years – old boy diagnosed with metastatic retinoblastoma. Blind in both eyes, the boy called me “mama”, an Indian word for uncle−smiling each time he left the OPD chamber. The word ‘uncle’ holds deep cultural resonance and I was moved with compassion. Holding her baby, she told me, “I know what his future holds. I just want him to be at peace when it happens.” Not once did she ask, “Why me, why my baby? Her grace and courage felt like a phoenix rising from ashes in the midst of resilience and radiated acceptance. Her spirits even healed my inner painful wounds just like a magic.

That moment revealed to me what palliative care truly is –

“When someone is in pain, despair or grief, even a simple gesture, like quietly sitting beside them, can soften, lighten and dilute their suffering. That wave of invisible grace, comfort or a sigh of relief, is what I call Palliative Care.”

Just like Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) doesn’t need a degree, palliative care too begins with instinct, presence, compassion, and a bit of wisdom. I began to see palliative care as a different kind of CPR (Caregiver/ Patient Rescue). It is a quiet reminder that even in evidence-based medicine, there exists a world beyond algorithms and clinical trials.

With rapid innovations and possible new solutions, medicine often runs ahead of us with new molecules, new scans, and updated survival metrics. This has created multiple specialties, super specialties and sub-specialties, paving the way for precision care. I have seen how powerful precision can be and in chasing it, I have also seen how care sometimes became fragmented, complicated, and diluted its shared wisdom of purpose.

As oncologists focus on regimens, markers and clinical trials, but we in palliative care speak the language of parallel planning, presence, and perspectives. It is not that one is more important than the other. It is that somewhere along the pathway, we stopped hearing each other.

“Palliative care is the integration of medical science with moral science. It is applied physiology with compassionate psychology. It bridges the quantitative with the qualitative — the biology of suffering with the biography of the sufferer.”

In India, especially in Tier II and III cities, the doctor is often the first and most trusted point of contact in a hospital and the advice often feels like superhuman to the people around. I believe, awareness must begin with practitioners. The issue is not really “what is palliative care?” but “why now, whom, and when?”

Through my own journey, I have faced both resistance and possibility, and each has pushed me to believe that palliative care must become a universal human right. In this process, I propose that palliative care can be compared to skin layers.

- Epidermis = primary level palliative care – something we all do every day- routine symptom relief, honest communication, and family support.

- Dermis=secondary level palliative care– specialist referral for moderate complexities involving advanced pain management, transitional care planning, and addressing compassion fatigue of formal and informal caregivers.

- Hypodermis=tertiary level palliative care focusing on complex symptoms including ethical ambivalence, emotional turmoil, terminal care, advance directives, goals of care, death care planning, and bereavement care.

Different lenses carry varied power, and so different teams amplify diverse perspectives. This is why palliative care should be a part of modern medicine-to hear those small things our mind tries to say when we were feeling broken or vulnerable. Palliative care is not about titles or hierarchy, its layered, anchored and integrated with the ongoing primary treatment irrespective of illness. To me, the real innovation lies in embracing the full spectrum and scope of palliative care without inhibitions and compromises.

India’s diversity in language, culture and tradition is mirrored in how people think, how they understand illness, and how they live through it. No one model fits all. The dynamic shift between hope and acceptance calls for precision palliative care−compassionate, individualized, and adaptable.

Despite advocacy and awareness, delivery and acceptance remain uneven. While many attribute this to policy or infrastructure deficiency, one vital ingredient is often overlooked: “emotions”. Emotions transcend policy. What one family accepts easily, another may take years, in some, never.

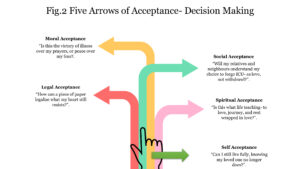

Through experience, I have come to recognize five kinds of acceptance that shape the journey of care spectrum.

- Moral acceptance– Is this the victory of illness over my prayers?

- Legal acceptance– How can a piece of paper legalize my emotions?

- Social acceptance– Will my relatives and friends understand my intention to withhold intensive care unit?

- Spiritual acceptance– Is this what life teaches- to be born, to love, to journey, and finally to perish wrapped in love? And what about the ones left behind- should they follow, or wait for their time?

- Self-acceptance– Can I live on without my loved one?

These forms of acceptance reflect conflicts within, waiting for someone to help guide through.

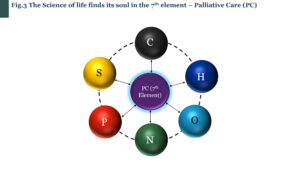

Science tells us we are built of six core elements – Carbon, Hydrogen, Nitrogen, Oxygen, Phosphorous and Sulphur (CHNOPS). But in my heart, I feel palliative care is the missing ‘seventh’ element – the one that gives meaning to our physical mass. To me, palliative care is a human commitment and responsibility, something we owe to one another irrespective of suffering.

The word “Palliative” originates from Latin, “palliare”, meaning to ‘protect’. On this World Compassion Day, may we remember that palliative care is not an option but a human commitment—a quiet revolution that protects what it means to live, to love, and to let go.

About the Author:

Dr. Ravi Kiran Pothamsetty is a Radiation Oncologist and Consultant of Palliative Medicine, leading the institutional palliative care service embedded within the Department of Medical Oncology, at Meenakshi Mission Hospital and Research Centre (MMHRC), Madurai, Tamil Nadu. It is one of the first such models in the region.